LARS is an acronym for Ligament Augmentation Reinforcement System.

Synthetic materials were first used in ACL reconstruction in the 1980’s to improve the strength and stability of the graft immediately post operatively, reduce donor site morbidity and eliminate the potential for disease transmission. The first synthetic ligaments were associated with high rates of failure and reactive synovitis. Over the last two decades with advancing technology, new types of synthetic ligaments have been developed. The latest LARS is composed of polyethylene terephthalate fibres, an industrial-strength polyester fibre. It can only be used in patients that have a well vascularised ACL stump, ideally in acute settings. The theory is that the LARS pulls the two ends of the ACL together and allow for fibroblastic in-growth. The synthetic ligament is used as a ‘internal splint’ that allows the torn ACL to heal around it.

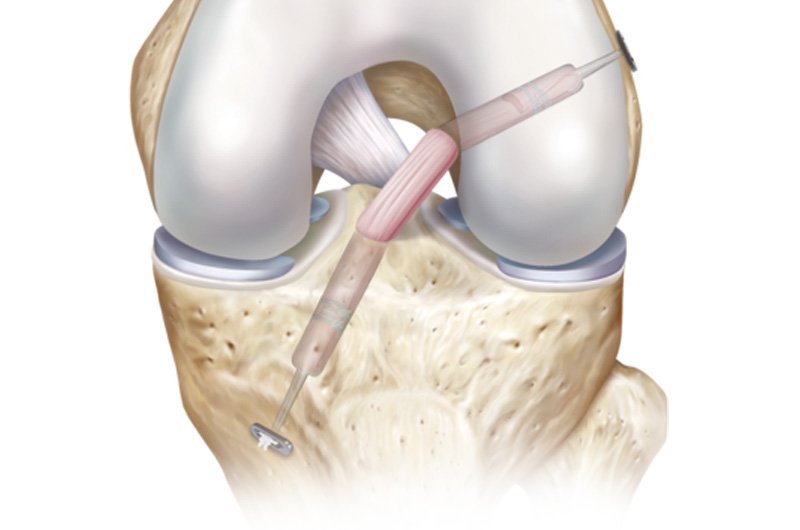

The Procedure

The ligament is highly cleaned to remove potential machining residues and oils to further encourage soft tissue in-growth and reduce the risk of reactive synovitis. The scaffold of the ligament consists of multiple parallel fibres twisted at 90-degree angles. This prevents the fibre breakdown and is thought to facilitate even tensioning of the graft fibres during knee movement. The scaffold provides a meshwork for the injured ligament to heal and repair.

Traditional ACL reconstruction techniques require debriding of the torn ACL fibres and synovial lining that normally envelops the ligament, in order to visualise the position for the graft. The LARS surgical technique uses an intra operative image intensifier X-ray to position the tunnels for the LARS through the ACL stump and is therefore able to leave the synovial lining and the torn ACL fibres insitu.

The proposed advantage of this technique is reduced trauma to the soft tissues of the knee and less surgical time. The ACL stump is anchored to the meshwork of the LARS to support it in an optimum position while healing. Overall, the LARS surgical technique aims to maximise in-growth of the original ACL tissue, thus preserving some vascular and proprioceptive nerve supply.

Good animated video of the procedure: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BYI3hCZMOK0

Benefits

- There is no need to harvest graft (hamstring or patellar tendon) from the already injured knee, so there are no graft harvesting complications & the proprioceptive fibres of the ACL are maintained.

- The surgery is minimally invasive.

- The post-operative protocol allows for an accelerated rehabilitation programme. Full weight bearing is encouraged the day following surgery; return to sedentary work is encouraged after a week; return to physical work and sport is allowed at 6-12 weeks post surgery.

- LARS ligaments can be used to reconstruct both the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments.

- LARS ACL and PCL ligaments come in many different sizes so that selection according to weight and activity can be precise.

- The LARS ACL has the intra-articular bundles in clockwise or anticlockwise orientation. This is to mimic the natural ligaments in the right or left knee.

Some Outcome measures:

KNEE STABILITY

Studies examining knee stability widely utilise the KT1000, and a good level of stability is a side-to-side difference in anterior translation of less than 3mm. At a 4 year follow-up, 73.9% of hamstring and 95.8% of LARS had less than 3mm of translation (Liu et al. 2010). Roe et al. (2005) showed that 82% of patellar grafts had less than 3mm of translation at 5 year follow-up. This suggests that in the short term LARS offers increased knee stability.

ACTIVITY LEVELS

Generally measured using the Lysholm Knee Scale and Tegner Score. Liu et al. (2010) found no significant differences between LARS and hamstring grafts at 4 year follow up. Roe et al. (2005) found no significant differences between hamstring and patellar grafts at 5 and 7 year follow up.

COMPLICATION RATES

In a 5 year short term follow up, there does not seem to be a major difference in failure rates. Gao et al (2010) showed a complication rate of approximately 6% at 5 years. Roe et al. (2005) suggest that there is no significant difference between patellar and hamstring graft failure rates at 7 year follow-up – approx. 20% for both. Interestingly, the study found those with patellar tendon grafts were more likely to rupture their contralateral ACL (18%) than ipsilateral (4%), whilst for hamstring grafts there was approximately even risk (10%) between legs.

Thanks for reading,

Annika Williams

Senior Physiotherapist

References:

- ACL Reconstruction With the LARS Ligament

- Roe J, et al. A 7-Year Follow-up of Patellar Tendon and Hamstring Tendon Grafts for Arthroscopic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction : Differences and Similarities. Am J Sports Med 2005 33: 1337

- Gao K, et al Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With LARS Artificial Ligament: A Multicenter Study With 3- to 5-Year Follow-up.

Arthroscopy – Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery (2010) 26 (4), pp. 515-523 - Liu Z, et al. Four-strand hamstring tendon autograft versus LARS artificial ligament for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) (2010) 34:45–49